When people talk about participatory design, the focus is usually on collaboration-getting users involved early, often, and meaningfully. But what’s often left out is motivation. What motivates users to participate in the first place? What makes them stay engaged throughout the process? And crucially, how do we ensure the final product continues to support their motivation once it's live?

These questions became central during my fieldwork designing educational tools with displaced and refugee learners. We weren’t just designing systems for them-we were co-designing with them. But co-design doesn’t automatically mean motivation. Many of our participants were initially hesitant: some lacked confidence in their “technical” contribution, some were overburdened, and some simply didn’t believe their input would have impact. Motivation had to be nurtured, both in how we ran the process and what we built together.

Embedding Motivation into the Design Process

In participatory UX work, motivation needs to be designed into the process itself. That means:

▪ Designing for autonomy in co-creation: We gave participants real choices-not just what colour they preferred, but how sessions were run, what features mattered to them, and how their contributions were recorded.

▪ Supporting competence during sessions: We built exercises around participants’ strengths. For example, parents who couldn’t read could still describe what a useful learning tool looked like or help design pictorial instructions.

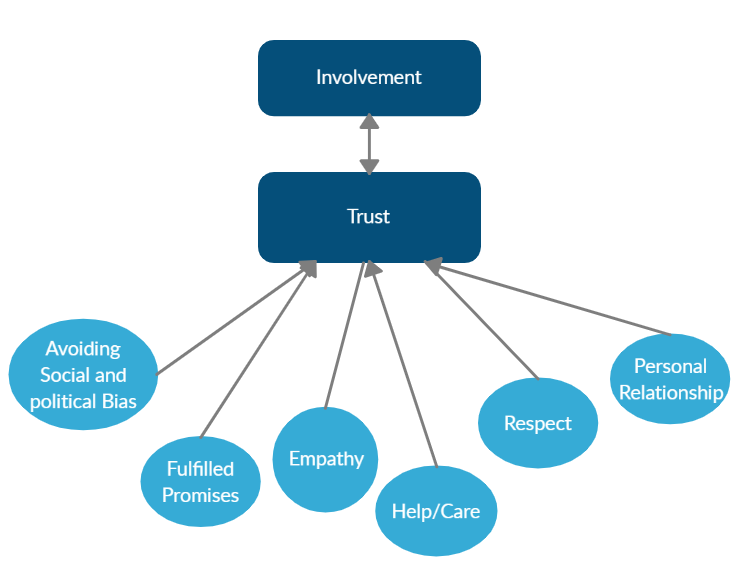

▪ Fostering relatedness among participants: We opened sessions with shared stories and peer reflection. This built trust and reminded people they weren’t designing in isolation.

The result? Participants became more invested, workshops became richer, and ideas were more grounded in community insight.

Designing for Motivation in the Final Product

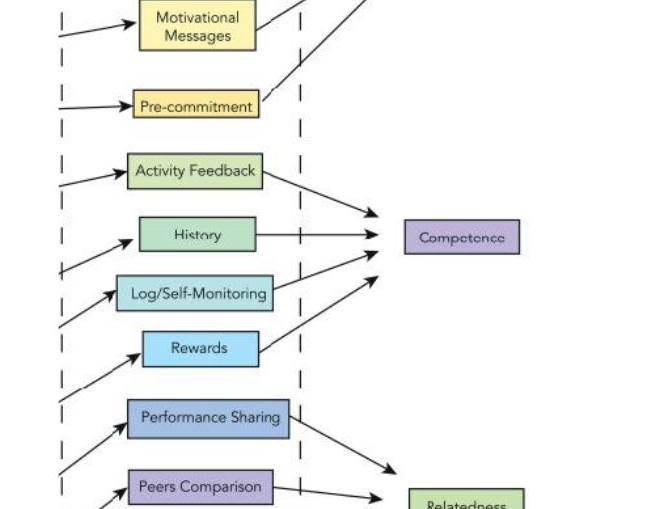

Motivation didn’t stop with the design process. We used the same Self-Determination Theory (SDT) lens when shaping the systems that participants would eventually use:

▪ Autonomy: Learners could explore lessons non-linearly and remix content, giving them a sense of control.

▪ Competence: Tasks were tiered with early successes designed in, and feedback was clear but non-punitive.

▪ Relatedness: We embedded peer stories and examples from nearby communities to create emotional connection.

This alignment between how we involved people and what we delivered made the product more than usable-it made it desirable.

Rethinking What Counts as Data

Even our approach to research methods had to shift. If we wanted real insight into what motivated our users, we couldn’t rely on conventional surveys alone. We observed engagement over time, analysed who came back to sessions unprompted, and gathered narrative feedback through casual, trust-building conversations. These weren’t just add-ons-they were core data sources.

In one case, a parent told us they felt like they were finally contributing “something useful and relevant to life outside the camp” to their child’s learning. That quote carried more weight than any Likert scale.

Takeaways for UX Research and Design

Motivation isn’t just something you design for in the end product. It should shape how you invite users in, how you run workshops, and how you collect data. It’s also a marker of inclusion. When users feel motivated, they feel seen-and when that motivation is supported through design, it leads to stronger outcomes.

Motivation isn’t a spark. It’s a thread that should run through everything you do.

Would you like me to illustrate these ideas with visual frameworks or a short field story from one of the design sessions?