In product design, we often talk about "engagement"-daily active users, click-through rates, time on task. But engagement doesn't equal motivation. Nudging users to do something isn't the same as making them want to do it. If you strip away the notifications and rewards, would users still care about the experience? That’s where motivation theory becomes critical.

As a UX researcher with a background in educational technology and human-computer interaction, I’ve often returned to one model to guide this thinking: Self-Determination Theory (SDT). It offers a more human lens on why people act-and what makes that action last.

Why Motivation Matters More Than Ever

In a digital world full of friction and distractions, it’s easy to confuse short-term clicks with long-term engagement. But designing for motivation means building something people come back to because they care, not just because they’re reminded or nudged. This really matters in areas like health, education, or public services-where long-term outcomes, not just one-off conversions, are the goal.

The Three Pillars of Self-Determination Theory

Self-Determination Theory identifies three universal needs that underpin intrinsic motivation:

Autonomy – Feeling like you have control and choice. Users feel empowered when they can pick their path, personalise things, or decide how and when to interact.

Competence – Feeling capable and progressing. Interfaces that offer clear feedback, guidance, and achievable goals help users build confidence.

Relatedness – Feeling connected to others. Features that foster community, let people share stories, or create emotional resonance can fulfil this need.

When these needs are met, users don’t just keep coming back-they feel supported.

How This Shaped My Design Approach

In my doctoral research, I worked on learning systems for refugee children in camps and Greek public schools. Motivation was one of the biggest challenges-these learners had experienced trauma, language barriers, and patchy education. Simply making the interface more ‘fun’ wasn’t enough.

Instead of gamifying for the sake of it, we used SDT as a foundation:

▪ Autonomy: Learners could choose from different formats-offline videos, web content, remixable modules. There wasn’t just one way to learn, and that gave them ownership.

▪ Competence: We introduced early wins-small tasks with instant feedback, so they could feel progress quickly. Tracking was lightweight but visible.

▪ Relatedness: We shared stories from similar learners, and highlighted progress across peers. Kids recognised their own community in the material.

Motivation went up. Learners showed more persistence, asked to take work home, and even came back outside school hours. Engagement wasn’t a hook-it was a reflection of purpose.

Applying SDT in Everyday UX

This isn’t limited to education. Across sectors, SDT provides a flexible lens:

▪ In banking, autonomy might mean letting users customise notifications or define savings goals.

▪ In health, competence could come from clear milestone tracking or jargon-free health feedback.

▪ In civic tech, relatedness might be as simple as showing users the impact of their participation on the wider community.

Applying SDT in Everyday UX

This isn’t limited to education. Across sectors, SDT provides a flexible lens:

▪ In banking, autonomy might mean letting users customise notifications or define savings goals.

▪ In health, competence could come from clear milestone tracking or jargon-free health feedback.

▪ In civic tech, relatedness might be as simple as showing users the impact of their participation on the wider community.

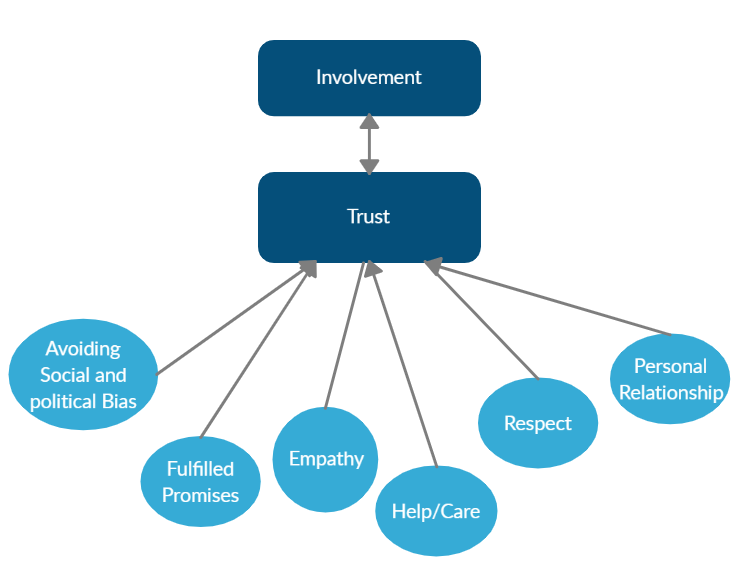

The visual to the right (click to expand), gives an idea on how various features and design elements can be mapped to the different pillars of motivation.

I myself tend to link the findings from my data analysis to the different aspects of motivation. An other article I am preparing for my blog also discusses how the different aspects of motivation can be used as a framework or design model for the data collection activities themselves.

Final Thought: Design for Why

When you design with motivation in mind, you’re asking better questions-not just “how do we get people to use this?”, but why would they want to come back? What’s in it for them, beyond the product itself?

Motivation isn’t something you wait for users to bring. It’s something you can help create.